Chief Kettle of the Squaxin Island Tribe

Written by Josh Miller, Squaxin Island Museum Library and Research Center

1/24/2020

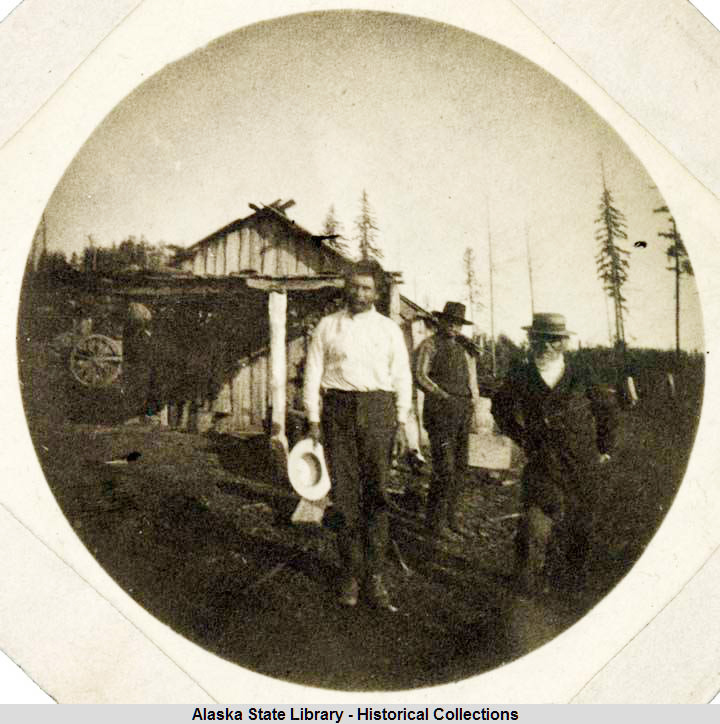

Louis Yowaluch (left), standing with Chief Kettle (right) on Mud Bay property.

Not much has been left recorded about the Squaxin Chief Kettle. He is found in the records under a variety of names including Kettle, Kethlid, and Labatum. Sometimes he is also referred to as Sitkum Kettle, potentially as a reference to his short stature. In Chinook the word Sitkum means “half”, but can also mean “short”, or “small” when referring to a person. Though he was of relatively short height, as evidenced by one of the few surviving pictures of him, he had a stocky build, and was overall a very sturdy man. Even into old age he was known to be agile, spry and strong, never letting his body keep him from pursuing his goals.

It is not known exactly when Sitkum Kettle was born, or where, but one family story tells of how he was born in Seattle during a Haida raid, in approximately 1830-1831. The movement of people was so rapid and unrecorded in the early 1800’s that no one can say for certain where his birthplace was. In 1910 an agent on the Quinault reservation made the claim that “‘Kettle Lobatum’ . . . was in reality a Satsop Indian”, based off Kettle’s relation to a Satsop chief named Swatser. What is clear, based on the record is that for the early couple decades of his life, or at least prior to the Medicine Creek Treaty, Chief Kettle lived on Case Inlet, near Sherwood Creek. This place, presently the town of Allyn, was settled by the Sherwood brothers who built a sawmill on the creek, affecting the salmon run in the process. Case Inlet was part of the original Squaxin homeland, and the inlet from which the name Squaxin was originally derived, being known by its native inhabitants as “Squawk-sin”. Shell middens which were used by the Squaxin people at the mouth of Sherwood Creek “extended 102 yards along the bank and varied from five feet to twenty feet in width”. Not only were shellfish a common staple food of the area, but salmon and deer were likewise plentiful.

Chief Kettle lived his early life similarly to how many people of the seven inlets would have lived: fishing, hunting, and harvesting shellfish in accordance with the seasons. He was also a prominent leader in his community. By the time of the Medicine Creek Treaty he had already begun being called Chief. Two other prominent community members, James Tobin and Mud Bay Sam, had this to say about Chief Kettle’s role in the community:

“Kettle was a man that was called all over pretty near all over from one end of the sound you might say to the other if there was anything going on wrong he was called to straighten it and marry people that was his business.”

For his entire life, or at least as far as is recorded about him, Chief Kettle spoke no English, and only a little Chinook. James Tobin once commented about Kettle, saying that “he only spoke Indian”. Despite this, he was able to foster an identity as a kind, genial leader, even amongst the white folks who knew him.

What gained Chief Kettle the largest boon to his reputation as a leader and peace-maker were his actions during the Puget Sound War of 1855-56.

Chief Kettle was an advocate of engaging peacefully with Euro-American settlers, and he remained resolute in that belief even after the Medicine Creek Treaty. According to Louisa Tobin, Sitkum Kettle’s daughter, when war broke out between the Medicine Creek nations and the U.S. in 1855, the chief wanted to protect his people from unnecessary bloodshed, and so he officially “surrendered his guns” to the Sherwood brothers on Squaxin Island. This was both to express good faith and to show that he had no hostile intentions. After he surrendered his guns, his family members were likely brought to the island where they stayed for the remainder of the war. They lost their homes and lush food sources on Case Inlet in the process, but they managed to avoid some of the bloodshed faced by the other Medicine Creek tribes in doing so.

A local newspaper in 1857, published shortly after the Puget Sound War – or Indian War as it was called then – had this to say about the Squaxin tribe at the time:

“In Consequence of the Indian war, we presume it is, that the treaty at the head of the sound, only, has been confirmed; and as a portion of the Nisqually and Puyallup tribes were hostile, only the Squaxen Indians have participated fully in its advantages. On the Squaxen reservation, the indian houses are nearly completed. A large field is enclosed, ready for cultivation. This field is being enlarged – a blacksmith shop is in full operation, supplying tools and impliments to the Indians. They will be supplied with clothing in the course of the season. Each family that will till, properly, the plowed field allotted to it, will have a bountiful supply of potatoes, peas, and other vegetables in the Fall.”

After the war, some of the folks who were originally from Case Inlet moved to the Skokomish reservation, due to the historically close relationship that existed between the Case inlet and Skokomish communities. Others, including the Kettles and Tobins, moved to Mud Bay and Oyster Bay with friends and relatives to escape the inadequate living conditions which existed on the Island, and to pursue economic ventures which would uplift them financially, specifically in oystering and woodworking. Chief Kettle would continue to be a prominent community leader for the remainder of his life in both Mud Bay and in Oyster Bay where he lived, known as both a strong voice of the people, and a kind-hearted, down-to-earth man.

After the war, Chief Kettle spent nearly all of his time in either Oyster Bay or Mud Bay helping his community in a variety of ways. In April of 1874 Chief Kettle and three other community members volunteered to help complete the Olympia-Tenino railway, and was acknowledged for his contribution in the Washington Standard News Paper:

“The head chief of the Squaxon indians, Kettel, with three of his chosen braves reported early yesterday morning to the forman on the grade of the Olympia-Tenino railroad . . . they manfully went to work.”

In 1879 Chief Kettle, then an appointed minister, performed a marriage for Harry Weatherall and Sallie Hall, a Case Inlet Squaxin relative of Kettle’s, on Oyster Bay. James Tobin had been asked by Harry to translate for Kettle and convey to him that he wanted to marry Sallie, because Kettle “only spoke Indian”. Apparently Kettle was not fond of the idea, and resisted for some time. As Tobin recalls in 1911, “The old gentleman didn’t want to marry them at all, because Bostons throw their women away and he didn’t want Sallie to live with him.” Tobin later remarked that Kettle “kicked on white people marrying Indians.” Harry persisted however, insisting that he wouldn’t run away, and that he wanted to be married in the style of “the Bostons”. Eventually, partly because of a change in laws regarding marriages between whites and Natives, and also partly because of some encouragement by Tobin, Kettle acquiesced and performed the marriage on the Tobin’s Eld Inlet property. Over three hundred Natives from around the sound and Neah Bay attended the wedding, and the Tobins provided all the food.

Once again in 1900 the Tobins and Kettles gathered for another wedding, this time between Edward J Smith and Katie Tobin, on Mud Bay. Like the previous wedding, a great many Natives who were famous in pioneering days were present, as were a number of local white folks who had become close with the families. Edward J Smith, as is noted in the news paper article commemorating the marriage, was one of the few remaining natives whose head was “flattened” during his youth. After the wedding ceremony and well-wishes from those in the crowd, an elderly native man stepped in front of the bride and groom, and gave a rousing speech in Salish. None of the white folks understood, but all the Native folks in attendance listened keenly to what was being said. Apparently, as an interpreter eventually related, the old man was Chief Duke of the Skokomish tribe, and he had known the groom, Edward, to be wily and rambunctious in his day. Apparently the chief had taken advantage of the occasion to “give the newly married man a talking to”, saying that he would have to knock off his boyish behavior, or else something bad would happen. Following this interaction, everyone lined up in front of the house for photo taking, and this is where the photo of the wedding was shot, wherein one can see Olympia Jim, Henry Martin, Edward Smith, Katie Tobin, Annie Tobin, and Mary Jackson Jim. Jack Slocum, Mud Boy Charlie, and many others were also in attendance, but are outside of the frame of the photo. Chief Kettle, for his part, refused to sit for his picture to be taken. Upon being requested, Kettle told them that “he never had been ‘taken’, and never would be.”

In the fall of 1903, Chief Kettle passed away suddenly at his home in Mud Bay after coming down with “LaGrippe”, or the Spanish Flu, the result of a bad cold he had contracted a few days prior. He would have been approximately 85 years old at the time of his passing, and his funeral was held at the James Tobin property on Mud Bay.

Today Chief Kettle lives on in memory as not only a prominent tribal ancestor to many families within the Squaxin and Nisqually tribes, but also as an example of what strong and genial leadership can look like. He took adversity and hardship and was able to work through it in ways that helped his community to grow and prosper despite the troubled times they lived in. He serves as a much needed example for the current generation of leaders, and for generations of leaders that will come after.

Sources Cited

Davies, Bruce. Tobin Cemetery. PDF File.

De Danaan, Llyn. Katie Gale: A Coast Salish Woman’s Life on Oyster Bay. Lincoln and London, University of Nebraska Press. 2013.

Gibbs, George. Dictionary of the Chinook Jargon, or, Trade Language of Oregon. New York, Cramoisy Press. 1863

Heffernan, Trova. Where the Salmon run, The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr. University of Washington Press. 2012.

Mason County Journal, June 22 1900: “An Up-To-Date Wedding.” Page 3.

Pioneer and Democrat, April 3 1857, Page 2 Column 1

Washington Standard Newspaper, April 18 1874, Page 2